|

SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE

In February 1999, AHRC submitted to us a

compilation of evidence detailing the charge that

militarization has caused food scarcity. Along with a series

of written depositions, it contained history, statistics and

excerpts from numerous reports about Burma’s government

and economy. Also provided were several explanatory maps and

a collection of photographs detailing aspects of the

evidence. After reviewing the compilation, the People’s

Tribunal convened in Thailand to hear testimony firsthand. On

April 2-4 twenty-six witnesses made depositions. We

interviewed nine of these people in Bangkok, and the

remaining seventeen in Tak Province. Most of the depositions

were recorded on audio cassette and later transcribed.

Witnesses who gave testimony in languages other than English

worked through interpreters, and their depositions were later

translated into English for documentary purposes. It is not

practical to insert all the evidence in this report. Instead,

we include a clear and representative sample. 1

Untold Sorrows: Food and War Untold Sorrows: Food and War

The evidence demonstrates that food

scarcity is a national trend which varies according to

regional political and economic conditions. Most notable are

differences between areas with armed conflict and areas

without it. Terminology differentiating these areas is

problematic. The government does not use the term "civil

war," preferring instead to consider the conflict an

insurgency by "illegal armed groups." On the other

side, opposition groups see the armed conflict as revolution

or even war for independence. It is outside the

Tribunal’s scope of inquiry to investigate and decide on

the conflict’s political classification; we are

concerned with the relationship between armed conflict and

hunger. In keeping with the general trend of the testimony

brought before it, the Tribunal uses the terms "civil

war zones" and "non-civil war zones," without

bias or obligation to any political significance they might

connote.

| Nevertheless,

terminology problems remain. Civil war zones are

often further divided into "black" and

"brown" zones, the former meaning areas

considered by the government to be outside its

effective control, and the latter denoting areas over

which its control is incomplete. It is widely

reported that this further division, along with the

term "white zone" for areas without an

insurgent challenge, is a fundamental military tactic

employed by the government. Both types of zone

experience consistent human rights abuse.

Furthermore, the term "free-fire zone"

declares an area to be under a form of military

control which allows soldiers to shoot anyone on

sight without the need to determine identity. Again,

the government doesn’t use these terms in its

public documents or mass media. Regardless of whether

these divisions originate from the government, the

Tribunal finds them logical and useful descriptors

for real conditions, and elects to use them here. |

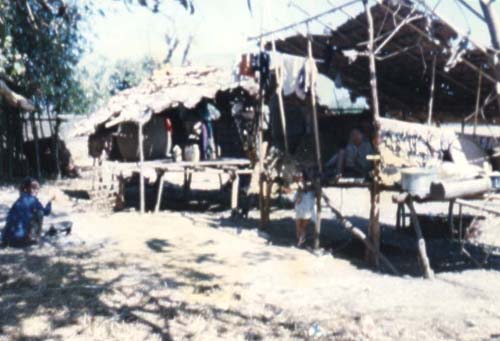

People

are forced into the jungle, hiding their rice and

struggling to survive without medicine, schools or

much contact with the outside world |

Food Under Fire Food Under Fire

Remote regions of Burma are exposed to

primitive but militarily effective scorched-earth tactics.

According to Tatmadaw strategy these are "free-fire" areas, in

which all people are suspected of insurgency and are treated

as the enemy. People are subjected to indiscriminate

executions and a panoply of other human rights abuses, mass

destruction of crops and villages and massive population

displacement. The Burmese army has devised what is known as

the "Four Cuts" strategy to deny rebels (1) food

(2) money (3) communication and (4) recruits. In practice,

the strategy does not differentiate between combatants and

civilians. To begin with, selected areas 40 to 50 miles

square are cordoned off for concentrated military operations.

The army then orders villages to move to strategic locations

under its control. Soldiers may warn that anyone who refuses

to move will be treated as an insurgent and can be shot on

sight. After the first visit, troops return periodically to

confiscate food, destroy crops and paddy and

shoot anyone suspected of supporting insurgents.

| The evidence

collected by Saw Kwe Say in respect to Papun and

Kyauk Kyi Townships describes how people are dealt

with in insurgent zones. While the army has its bases

in the lowlands, people are forced to live in the

jungle "hiding their rice and struggling to

survive without medicine, schools or much contact

with the outside world." People say that they

are always on the run for they do not know when the

soldiers will come. They face immense hardship: |

Map 5: Pegu Division

(Click to view full image)

|

| |

|

| "This

year we ran from the army four times. The third time,

they pulled all the paddy stalks from the ground and

burned down the field hut" |

When the army columns come

into the mountains, they destroy any houses they

find, shoot whoever they see, and take or burn all

food and possessions. If they come to a village, they

don’t see any people because everyone has run

into the forest already. If they find rice stored in

the jungle, they take or burn it, or sometimes lay

land mines around it. We always look for a safe place

deep in the jungle to hide our food…These hiding

places may be safe from soldiers, but not from

wildlife. 2 |

Because of these harsh military pressures

in an already difficult natural environment, the villagers

constantly struggle to feed themselves:

| One woman in my

mother’s village was growing rice to feed her

four children. The soldiers came so she abandoned her

small field for a while. As a result the crop

wasn’t very good. Before harvest, a pack of wild

boar came and destroyed about one fourth of her crop.

After harvest, we left the cut rice stalks to dry in

the fields, and the boars came back for another

quarter. Finally, when we were preparing fields for

the next crop they came back again. When she saw what

had happened she just sat down, stared at what was

left of her rice and began to cry. |

Picture 11: "The rice they couldn’t carry

away, they set on fire

|

Saw Kwe Say appeared before us and

submitted further information he collected relating to a

village called T’kwiso, where villagers said:

This year we ran from the army

four times, and three times in September they really

reached our location. The first time they took all our

possessions. The second time they destroyed all our

crops. The third time, they pulled all the paddy stalks

from the ground and burned down the field hut.

He stated that this year families would

face extreme hardship from the soldiers coming and destroying

the grain and foodstuffs, and also from having to flee.

Displaced people have little forewarning

and little time to prepare food for their stay in the jungle.

Even their food can become a liability, as reported during a

1997 military operation in Kyauk Kyi Township:

The villagers of Nwar Lay Khoh

knew that troops were approaching, so they began to

evacuate their houses. They fled into the scrub,

dangerously close. They had to kill roosters and geese,

because their cries travel far and might reveal the

hideout. For security, dogs too were beaten to

death—there is a lot in the jungle to bark at. 3

According to another researcher, Dee Gay

Htoo, as the army passes through villages it

indiscriminately destroys food. He states that:

The biggest problem is getting

food. Troops have destroyed virtually everything of last

year’s crop and now people are trying to plant, but

there hasn’t been any rain, so the crops are poor.

The suffering is extreme. Most people are living only off

bamboo shoots and other roots.

Dee Gay Htoo filed another report in

October 1998 which details military attacks on other villages

in Papun. For example, in Tei Bo Plaw Village:

| Battalion 706 burned

down two sections of Tei Bo Plaw. Khler Hat Htah

was destroyed on 31 October 1997, and Maw Pho Khi

on 12 November. Twenty-two houses were burned.

The army stayed in Tei Bo Plaw for about one

week. The villagers fled into the forest but

couldn’t take much food. Altogether, 71

barns were burned, and the people lost 3,692 baskets

of grain. 4 |

Map 3: Karen State

(Click to

view full image)

|

In another village, Doh Daw Khi, Dee Gay

Htoo continues,

When the villagers fled, they

couldn’t take very much food with them. They fed

what they had to the children, and the adults fasted.

They went and secretly grabbed food now and then. One

woman gave birth during this time, but the child died,

due to the conditions in the forest. These villagers have

had to hide out there for five months, the entire rainy

season. Most are animists whose religion stipulates that

any place destroyed by fire cannot be rebuilt for three

years.

| In this way, we have details of

several villages destroyed by the army in Papun

region. There is also a report by Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) which lists 105

villages forced to relocate, 180 burned down and 10

more partially destroyed. 5 |

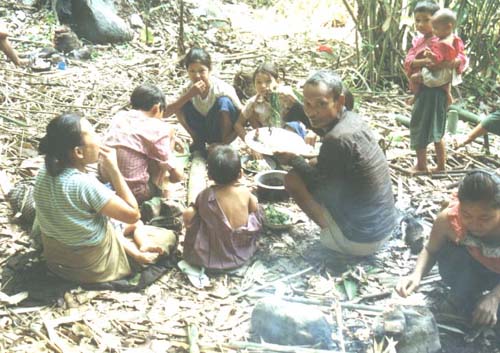

Picture

12: "The people live in fear that the army will

search and find them."

|

From Kyauk Kyi Township we heard similar

allegations of army abuse. Saw Kwe Klo reported that the army

..looted and destroyed property

in every village they entered. They arrived in Nwar Lay

Khoh on March 14, and burned down 32 houses. They ate all

the ducks, chickens and pigs they saw. The people work

swidden farms. The land must be prepared in February, but

because of the army people didn’t come back until

May. This has meant a very poor crop... 6

Picture 13: "I saw one family

close to utter starvation,

the two small children crying from

hunger."

|

"The biggest

problem

is getting food.

Troops have destroyed

virtually everything of

last year’s crop...

The suffering is extreme." |

There are many instances of similarly

tragic experiences narrated by villagers. Hunger can force

unarmed civilians into deadly encounters with the army. On 3

April 1997, soldiers entered Thay Khoh Mu Der, whose

inhabitants evacuated immediately

without preparing any food for

themselves. They had nothing to eat in the forest. The

army burned 36 houses and 14 barns containing 200-400 baskets each.

Some villagers decided to come back for hidden rice. Five

men fearfully returned, but the soldiers saw them and

started to shoot. Phar Khin Sein, aged 50, was killed and

the others escaped. 7

Saw Htoo K’baw, a teacher from Papun

Township gave his statement to Saw Khwar Hsit, a Tribunal

researcher.8 They

both appeared before us on April 4. Like most of the people

from his village, Saw Htoo K’baw came to Thailand two

years ago. In his first statement he recalled, "Starting

from January 1992, the Burma army soldiers began to battle KNU there and destroyed

villages. They patrolled and skirmished, and so 1992 was the

first year that there were food problems." However, he

stayed on even when others had left. He gave a year by year

account, starting with his own efforts to earn a living

during the school break:

In January I planned to trade in

biscuits, Ajinomoto and

clothing to get extra money. The soldiers were patrolling

because of this trade, and would stop people on the road

or shoot from far away. As five of us were returning,

some soldiers off to one side of the path saw us and

shot. We dropped our goods and ran for our lives. I lost

all my valuables and was discouraged from trading any

more.

Thus, his search for food was confined to

the village and its immediate environs, which added to

hunger. Starting from September 1994 his family fled the army

frequently and

had to eat rice porridge for two

months. After October we reopened the school, but on

weekends I found work sawing timber in order to buy rice.

I didn’t even want to plant rice anymore at that

point. Sometimes all we had to eat were boiled bamboo

shoots and roots.

Eventually, Saw Htoo K’baw took up

farming again, but his efforts to grow rice were continually

frustrated by military action:

It was almost harvest time when

we fled to where there was no food. We had not brought

much with us, so we ate porridge. For two or three months

we hid like that, and my fields were destroyed.

By 1996, conditions had become miserable

for the whole village. As an immigrant to the area, Saw Htoo

K’baw wasn’t adept at hunting or foraging for wild

roots and vegetables, which is how the indigenous people

coped with hunger. He turned to his neighbors for charity:

| I would forego food so

my children could eat. I went around begging for

rice. Some people took pity and gave me a cup or

two. Most who had migrated to the area like me

were suffering considerably. |

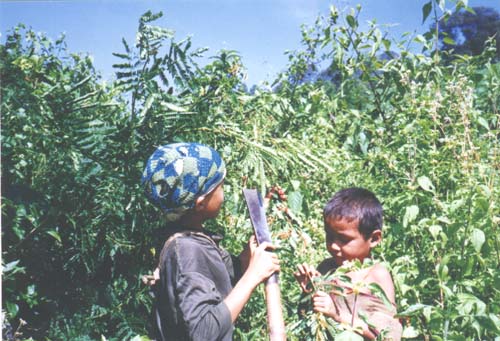

Picture

14: "In the jungle we had to eat roots and

leaves."

|

His family continued to survive without

food security, but conditions were dire. In 1996 they took to

the jungle three separate times, during which he saw others

suffering an even worse fate:

Each time we had no food. In the

forest relationships varied. Some shared food with others

then left to look for roots together; others did not. I

saw one family close to utter starvation, the two small

children crying from hunger. The mother pitifully fed

them roots which hadn’t been boiled long

enough—she probably didn’t know what else to

do. After that they suffered nausea, vomiting and

diarrhea.

Eventually they could withstand no more.

Losing their home was the last straw:

Around April, it rained very

heavily and our house collapsed into the river, totally

destroyed. We were left with nothing, no food and no

place to stay, so we fled and hid. My children were sick.

A KNU

official gave me some rice. I thought about the situation

and knew we couldn’t stay there anymore, and so we

came to this refugee camp.

When we met Saw Htoo K’Baw in April he

testified that between 1994 and 1996 up to thirty children,

mostly under 5 years old, died from malnutrition. We asked

whether he would go back, and he answered:

Picture 15: "We cannot go back, we dare not go

back and face the soldiers."

|

Everyone wants to go back,

but is afraid. Even if we went and there were no

soldiers, we would still have a food problem in the

first year or so. Also there are a lot of landmines,

planted by both sides. If there weren’t mines,

it would be more feasible. |

We have videotaped statements from several

people in Papun, all narrating the same story of destruction

and flight.

Another informant told a similar tale of

military abuse in Myawaddy Township, who reporting that when

soldiers came they

Picture

16: "In the forest relationships varied. Some

shared their food with others then left to look for

roots together

|

ate our pigs and chickens.

Anything that they didn’t eat, they killed, and

the rice they couldn’t carry away, they set on

fire. Day to day, we could still eat, but over a

longer time we would surely have starved. Because we

couldn’t travel around, we couldn’t work.

We always had to follow their orders. My children

suffered from diarrhea and malaria. So before my

family reached the point of starvation we fled to

this refugee camp. If I had stayed in my village I

would surely have died. There were still 20 baskets of

threshed rice in my barn. I had to leave all that. 9 |

The above evidence comes

from Karen State, but conditions are similar in central and

southern Shan State. AHRC’s

compilation shows that since March 1996, the Tatmadaw has

forcibly relocated over 1400 villages through 7000 square

miles. Over 300,000 people have been ordered to move at

gunpoint into strategic relocation sites. The relocations

intensified in 1997 and 1998, with people in new areas forced

move, and existing sites forced to relocate yet again. Vast

areas of 11 rural townships have become depopulated

"free-fire" zones. One witness described to us

relocation in Shan State:

Three to five days after the

order, soldiers come back. If villagers haven’t

left, either they say ‘go now,’ or burn the

village, or shoot—there are many different

scenarios. Out of 300,000 people, 100-120,000 have come

to Thailand. About 100,000 are in relocation sites, and

about 50,000 are on the outskirts of towns where they can

find work or have relatives. About 50,000 are hiding.

They are trying to survive in the jungles. 10

The Tribunal also heard of a family’s

struggle with relocation, hunger and violence in Shan State.

Her family

| was relocated to Kun

Hing in 1996. They went to the relocation site

and tried to stay, but couldn’t. They went

back into hiding after a year, on a heavily

wooded island in the river. Her father would

catch fish at night then secretly go to Kun Hing

to sell in the market. Just last month he went

back to his old village to look for cattle he

left there. He was shot and killed. The family

lost their breadwinner, so they moved to Kun Hing

and the mother sent her to Thailand to earn

money. |

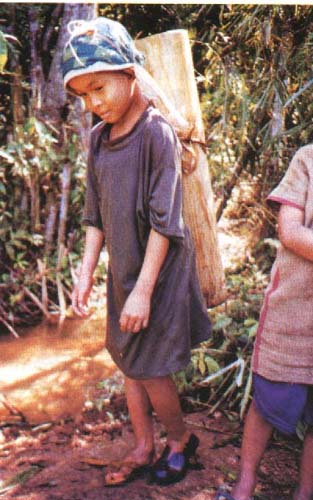

Picture

17: "People are forced into the jungle,

hiding their rice and struggling to

survive."

|

Villagers in the relocation sites work as

porters, build roads, dig ditches and erect fences at nearby

military camps without food or pay. Most of the relocated

people are farmers; so all these changes have seriously

affected regional food production.

Similar is the situation in

Karenni State. The Tribunal heard that

large numbers of Karenni farmers currently live displaced.

Some have moved to the relocation camps; the majority remain

hidden in the jungle; and some have fled to refugee camps in

Thailand. Many see no viable option in Burma and migrate to

Thailand to live as refugees or illegal migrant workers.

The relocations about two years

ago in Karenni State involved 70-80,000 people, entire

regions were moved. People had four choices: 1) go to the

relocation site, under Burma army control; 2) stay with

relatives in town; 3) hide in the forest; 4) cross the

border into Thailand, the last resort. The vast majority

of people don't want to come. Many went to the relocation

site at Shadaw. Now, two years later, people are arriving

in Thailand because they simply could not survive. They

tried. There are people who said their father starved to

death, people who said, "This does not happen in

Burma, people do not starve." They tried to make

ends meet, they cannot any longer, and they come to the

border. 11

The AHRC has summarized how the civil war

creates food scarcity. It identified six factors:

- Direct

attacks on civilians and food

Military offensives destroy villages, farms, grain

and livestock. Food is consistently targeted for

destruction. Civilians displaced by combat who return

to their fields risk being shot on sight. Some

communities are attacked more than once within a

year.

- Looting

of food and possessions

Soldiers take food and livestock without permission

and loot other household possessions.

- Displacing

people

Civilians flee to the jungle, become internally

displaced persons (IDPs), and face food shortages.

Army columns destroy any hidden food they find.

People hide in the jungle as long as they can. When

they can no longer survive this way, they try to flee

from the area completely.

- Restrictions

on trade and travel

The army cuts trade and transportation routes to

"black" zones, creating shortages of food,

medicine and other essentials. Civilians are also

denied income through trade.

- Ecological

damage and crop shortfalls

Frequent military incursions diminish soil fertility

by preventing farmers from preparing their fields

properly. Military action also interferes with

planting, tending and harvesting crops. Therefore,

farmers produce a shortfall of paddy and other food.

- Poor

health

Civilians, particularly children, suffer from

malaria, diarrhea, anemia and malnutrition. The

evidence links child mortality to food scarcity.

Non-government clinics in "black" areas are

military targets, and trade in medicines is

prohibited, thus denying treatment to the ill.

To Live, to Work, to Eat To Live, to Work, to Eat

In areas not entirely controlled by the

government, we find systematic population displacement and

forced labor, arbitrary taxation, extortion and other

infringements on basic economic rights.

The Tribunal heard testimony about the

typical problem of two or more armies vying for

administrative control. According to a woman from Mon State,

military demands piled up with each new regime:

The village was taxed by KNU for a

long time, though there were some benefits, such as

schools and clinics. When the Burma army came it also

made demands, but if fields were not destroyed then we

could pay. But with the advent of DKBA in

1996 food problems have grown. 12

Similarly, we read evidence of how

civilians are caught between insurgents and the government.

In 1996, the Tatmadaw announced the following fines and punishments

people in southern Burma’s Thayet Chaung Township:

- Any

village where insurgents fire a gun must

relocate within seven days.

- If

insurgents attack Tatmadaw territory, all

villages through which they passed must move.

- If

any Burma army soldiers die in combat, the

nearest village must pay compensation of

50,000 kyat for each

dead soldier.

- If

insurgents take Tatmadaw equipment or food,

the nearest village must pay to replace it.

- If

Tatmadaw loses guns, the nearest village must

pay 15,000 kyat for each.

- Any

village where a battle takes place or where

insurgent supporters are exposed will be

burned to the ground. 13

|

Map 6: Tenasserim Division

(Click to view

full image)

|

Most of Tenasserim Division is a contested

area. AHRC has submitted that severe military action since

1997 has displaced much of the rural population. These

effects have been documented in various reports such as

"Tennasserim Situation Report" (1998) by the KNU Mergui-Tavoy

Information Department and "The Situation of the People

Living in the Gas Pipeline Project Region" prepared by

Mon Information Service (1997). All detail how villagers were

conscripted for forced labor on development projects under

appalling conditions. Moreover, they had to feed themselves

while doing it. Much of this farming population has either

been forcibly relocated or if not, subjected to severe

restriction of movement. Many are prohibited from staying

overnight in their fields, necessary during the

labor-intensive planting and harvesting seasons.

We received statements on the fear created

by this constant military presence. Naw Ble, a subsistence

farmer in Dawei

township, reports that she returned home after the army

promised not to harm villagers:

| We saw all our

possessions scattered, and no cock crowed, no dog

barked, no cat cried and no cattle wandered about

the place. Everything was quiet. The next day,

troops started to dig trenches by our houses.

They did not harm us, but would climb our trees

and take fruit. They ordered us not to leave the

village without permission. To go out cost 15 kyat

per day, and we had to be back before dark. 14 |

Picture 18: "It was almost harvest time when

we fled to where there was no food.

|

We found that counter-insurgency measures

include the confiscation of food from civilians. The same

witness related how her village’s food was taken away:

| After wandering in the

jungle we felt there were no more places to go.

Some people suggested going back would be better

than being caught in the jungle. So one day when

there were no soldiers in the village, we

re-entered… They ordered us

to bring our paddy from where we hid it, or they

would find and destroy it. Some brought the rice

and it was confiscated. The soldiers ate it. At

the same time, soldiers went house-to-house

selling ration rice for 50 kyat a pyi.

We pay to work our own plantations, we serve them

without wages, our paddy is looted then we buy

back rice to survive. Our fruit and crops are

taken, our animals and plants are taken, we are

unable to escape. They told us troops in the

hills have orders to kill anything they see. We

are haunted by this.

|

"We

saw all our possessions scattered, and no cock

crowed, no dog barked, no cat cried and no cattle

wandered about the place" |

This treatment by the military naturally

created resentment among the people. Another villager

complained:

Picture

19: "They ordered us to bring our paddy from

where we hid it, or they would find it and

destroy it."

|

I feel bitter about the

troops staying in our village, looting our rice

and eating it, then selling us their rations. We

have very little money to buy rice. Think about

it! How long can you survive without any time to

earn money? 15

|

Adjacent to combat zones, "brown"

areas are a constant source of conscripted labor. The army

forces people to work continually, a practice well documented

by international organizations. The International Labour

Organization’s exhaustive report commented on the

economic ramifications: 16

Picture

20: "We slept soaked."

|

Forced labour caused the

poorer sections of society who carried out the

majority of the labour to become increasingly

impoverished. Day labourers needed paid work

every day in order to obtain sufficient income

and that became impossible when they were forced

to provide uncompensated labour. Families who

survived on subsistence farming also required

every member of the family to contribute to this

labour-intensive work, particularly at certain

times of the year. Demands for forced labour

seriously affected such families. Families who

were no longer able to support themselves often

moved to an area where they thought the demands

for forced labour would be less; if this was not

possible, they would often leave Myanmar as

refugees. Information provided to the Commission

indicated that forced labour was a major reason

behind people leaving Myanmar and becoming

refugees. |

Furthermore

porters on duty go hungry, as recounted by this 18 year old

from Kawthaung Township who was forced to carry loads for an

army column in 1997:

All the

porters became weak from lack of food. I saw about ten

fallen by the way, some were ready to die, rolling around

and murmuring. Some had swollen faces and heads. Seeing

this I was afraid, since I was weak and could not walk

well. I wanted to run but did not know the way, so I

carried on even though weak and thin. 17

Another porter serving at the same time

echoed this ordeal:

They fed us two cups of rice a

day, along with salt and sometimes banana palm shoots.

The soldiers had enough rice, curry and canned food. More

than 100 porters slept in a shelter we built ourselves.

The roof was made from old iron sheets. When it rained

the roof did not cover us, so we slept soaked. There were

so many sick porters among us. The military didn’t

care for the sick. 18

| We also saw a report on Palaw

Township, where the people are caught between the

Burma army and KNU. The Tatmadaw suspects villagers of helping

KNU and targets them for all sorts of torture,

extortion, and confiscation of food. Thus, many

villagers are hiding in "free-fire" zones.

These people live in fear that the Burma army will

search for them and find them, especially in the dry

season. In fact, in the 1998 dry season troops

destroyed many jungle plots, and barns, livestock and

property were confiscated. The main concern of these

internally displaced people is food. The AHRC has

also collected several statements from the affected

persons. 19 |

Picture

21: Many villagers are hiding in

"free-fire" zones

|

We read case studies from Bilin Township

and Pegu

Division. These are areas where people have been forcibly

relocated. According to one relocated villager, arbitrary

taxation, forced labor and restricted movement result in food

scarcity:

Most villagers travel two or

three hours to work their farms. Traveling back and forth

they can’t really tend their crops, which get

damaged by disease, insects and weather. Soldiers moving

from one place to the next also trample the fields.

Swidden fields must lie fallow before being used again,

but because of relocations more people are forced into a

small area, so soil quality is deteriorating. Before the

harvest is in most people eat rice porridge, perhaps once

per day, with a few bamboo shoots, with parents going

hungry so children can eat. 20

Picture 22: "They threaten that if anyone shoots

at them in the village, then it will become

ash."

|

We also saw evidence of how

soldiers ordered farmers throughout eight villages to

pay "gardening taxes" on their own trees.

The fees were calculated as follows: 18 kyat for each

betel palm, 10 for a coconut palm, 15 for cashew, and

5 each for mango, jackfruit, pomelo and lime trees.

The army threatened the villagers that failure to pay

meant land confiscation.21 |

AHRC identifies nine conditions which cause

food scarcity in such areas:

- Direct

attacks on civilians and food

The army attacks civilians and food less frequently

here than in black zones, but burning of food, houses

and fields continues. Populations deemed

uncooper-ative experience the worst forms of military

excess.

- Expropriation

of food, possessions and land

The

army constantly demands rice and livestock, either

without paying or paying little. Soldiers resell

military rations while living off food stolen from

villagers. Bullock carts are confiscated for work on

infrastructure projects. Agricultural land is taken

for roads, plantations, barracks or military-run

development projects.

- Relocation

Forced

relocation of villages is common. Movement at

relocation camps is tightly restricted, while former

village sites are declared "free-fire"

zones. Trading may be prohibited. Farmers are denied

access to their fields. Those who flee relocation to

hide in the jungle expose themselves to free-fire

conditions.

- Forced

labor

The

army conscripts unpaid labor on infrastructure

development projects. Villagers perform menial duties

for the military and portering increases. People have

not enough time to work for themselves, and

self-sufficiency in the rural economy dissipates.

- Taxation

and fees

Furthermore,

the army levies arbitrary taxes and fees, including

fines for defaulting on labor conscription. These

payments cover expenses, surcharges and fines imposed

by local authorities.

- Crop

procurement

In some areas, the military enforces a version of the

national paddy procurement system (discussed below),

straining rice supplies.

- Rice

rationing

The

army confiscates and stockpiles rice, then rations it

back to farmers. Restrictions on movement, distance

between army camps and relocation centers or

villages, and corruption prevent these rations from

reaching civilians.

- Abandoned

farmlands

Economic

and military pressures force many farmers to leave

their land. The quality of vacated land deteriorates

rapidly, so that it may not be successfully replanted

immediately.

- Inadequate

health care

Stringent control on travel, possession of medicine,

and a general lack of services means that health care

is very poor. Existing clinics may have no trained

staff or medical supplies.

No War, No Peace No War, No Peace

| We also heard evidence from beyond

the areas of conflict. In Burma’s non-civil war

zones, failed agriculture policies and persistent

demands for cash, goods and labor undermine food

security. Witnesses testified to rising prices,

falling wages, unbearable taxation and the inability

to feed one’s family. We divide the evidence

into rural and urban areas. |

Picture

23: "Most villagers travel two or three hours to

work their farms."

|

Trouble in the Rice Bowl Trouble in the Rice Bowl

We heard myriad evidence attesting to

hardship in rural Burma created by government agricultural

policy, especially regarding production and distribution of

lowland paddy.

Much of this data comes from lower Burma: Mon State, Pegu

Division and Irrawaddy Division.

A 24 year old landless worker from Mon

State’s Thaton District described how taxation,

government policy and forced labor created hunger in his

village

This is a general description of

my village since 1988, but things have been worse since

1996 than any time before. The village has only about 18

real landowners, and the rest are hired workers. The

biggest farm is 50 acres. I worked on a 13 acre holding,

which yielded 60-70 baskets of

rice per acre, as long as we used fertilizer.

High taxes and hunger forced

some farmers to sell their land. They have to pay

the annual quota, which the government buys at 150 kyat per basket. The

administration had us build a big dam, and to support

this work farm owners paid one more basket per

acre annually to the township council. The dam

construction began in 1992 and took two years. The water

is for the dry season crop. The dam needs maintenance,

and if you don’t go you are fined 100 kyat per day.

Government plans to increase rice

production included chemical fertilizers and farm machinery

as well. Because of corruption, however, farmers did not

benefit from these enhancements:

Map 4:

Mon State

(Click to view

full image)

|

The Ministry of Agriculture and

Irrigation sells two kinds of fertilizer which farmers

can buy on credit at 3,200 kyat per

acre. But our township council prefers selling to

merchants, leaving farmers with only 4 bags for 10 acres.

But when the debts are due, farm owners have to pay the

full value, as if they had actually received 2 bags per

acre. We heard that the government sent irrigation

pumps, but after the township council received them all

the pumps disappeared. |

Apart from farming, the

people must work on a variety of projects run by the

military. Some, such as roads, are public works projects,

while others seem to be soldiers’ private concerns.

| Villagers build roads

without pay. If you don't go, the soldiers make

you a porter to the frontline. IB

33 Commander Aung Ye Min established a rubber

plantation on 500 acres near the village. The

army made people plant trees then fence in the

plantation. Cattle used to graze there, and now

if they stray back the soldiers shoot and eat

them. |

Picture

24: "Villagers build roads without

pay."

|

So, even without

insurgency, rural people face local military rule and hunger.

The witness described food scarcity in his village:

Taxes and oppression are

starving the village. There’s no time to work, only

to pay taxes and do forced labor; many villagers have

little food. Some must eat porridge, some only water

skimmed off boiled rice, and others only sweet potatoes.

To feed the children some adults go without food for

one or two days at a time. Even so, children increasingly

suffer diarrhea, sore stomachs, and death.

| "They

said, ‘If you can't stay then get out—we're

just following instructions. You farmers are

dishonest. When you need something we give it, then

you protest. We can't follow your whims any

more’." |

Picture

25: "Taxes and oppression are starving the

village."

|

Living under these

conditions, the informant’s own family did not eat

adequately. Food security eluded them, despite their

collective efforts. In the end, he left home to find work

abroad:

I have 5 children. My oldest

daughter, who is eleven, always went to do forced labor

while we parents looked for food. You see children 8 or 9

years old working. Sometimes we only had enough rice for

porridge. I worked all day, then went home only to hear

my children cry from hunger. My tears fell, too. I could

not suffer the poverty of my village. I came to Thailand

to work and send money home, so that they can eat.

22

We read the statement of a

58 year old widowed farmer from Rangoon Division. This very fertile area

had always enjoyed a rice surplus. She related the hardship

caused by government policies to increase rice production

through irrigation and double cropping. The drive to grow

more paddy began with forced labor:

The government made us dam the

Ngamoeyeik River then called on us to grow summer paddy.

The construction site was 5 miles away, and we walked

back and forth every day in the hot season, when it was

really stinking hot. Each family in the region had to

send people to dig. I heard that one pregnant woman died

carrying loads of soil on her head. I had to hoe the

ground. The work was enormously tiring. After we went

home in the evening, they videotaped the day’s

progress. The dam opened in 1995. 23

The dam now complete,

farmers had to adapt to the hastily-planned new crop:

Summer paddy started in 1996.

They didn't give seeds, we had to buy them. I'll tell you

something, they made us buy seeds taken from other

farmers. But different strains of rice were all mixed

together, one from here, one from there. When we planted

we didn't notice the difference, but they grew at

different rates. There were three different kinds of

rice, so what can you do about that? You can't do

anything! You would have to harvest one field three

different times, which is too much work. Farmers were

furious—some destroyed the whole lot and planted

beans or sesame, then bought paddy in the market for

their quota.

Despite these initial

setbacks, the government enforced the summer crop program.

Farmers were forced to comply:

Well, by this time most monsoon

paddy had been harvested, and people had planted their

beans. But with the dam finished everybody had

to grow summer rice. They told us we couldn't grow nuts,

we had to grow paddy. Officials from Rangoon, not

soldiers, came and ripped up the beans and even

unharvested rice. That was just about the last straw. The

government said, "We are making you grow summer

paddy for you yourselves to eat." They said monsoon

paddy is for government and summer paddy would be for

farmers.

But flaws in the program

continued to frustrate farmers and government alike,

particularly irrigation problems:

Picture

26: "The summer crop is a total loss for

farmers, but if you don’t do it, the government

will take away your land.

|

When we needed water they

didn't open the dam; when we didn’t want water

they gave it! At first they didn't release water as

some people hadn't finished harvesting all of their

crop. Summer paddy needs water, so the government

opened the dam and way too much water poured out.

People who hadn't finished harvesting their first

crop rushed out to gather it all up. In bean fields,

water flooded the landscape. Villagers asked,

"What are you doing? We can't even live here any

more." Then the government answered "If you

can't stay then get out—we're just following

instructions." Later they cut the water and the

summer rice started drying up in the fields. People

ended up pumping in water themselves, which was

expensive. The administration said, "You farmers

are dishonest. When you need something we give it,

then you protest. We can't follow your whims any

more." The authorities said farmers are

inconsistent and don't do things right. |

Eventually, farmers

confronted the state:

| Farmers were now losing

their crops. So villagers went to break open the

dam themselves. The authorities became

angry and said, "You went to break open this

dam, so you must relocate!" The village

leaders outlined their case step by step, then

the authorities understood a little. We didn't

have to relocate, but we had to help repair the

dam. We nearly died in the stinking hot weather.

Anyway, it was all flooded and the paddy was

dead, dead, dead. They took video where the crop

looked good, where it was green and ripe. They

don’t shoot the stuff that didn't

grow—you can't say anything about that. The

wet paddy smelled foul. The procuring agents

refused to take it. Nobody is producing enough

grain. No farmer has enough to eat. This is what

I know from my own experiences and what I myself

have witnessed. |

Picture 27: "The government said, ‘We

are making you grow summer paddy for yourselves

to eat’."

|

Amid this fiasco, farmers

still struggled to meet the rice quota. The widow’s

family faced insurmountable problems:

My son-in-law and I owed 80 baskets to the

government. His 6 acres produce about 200 baskets in a

good year. But this year he got less. The government

calculates quota by stripping stalks until the grain

fills a tin can. Where there's dense growth two or three

stalks will fill a can. They said that one acre would

produce 80 to 90 baskets. That's what they said... 80 to

90 per acre, compared with 200 for the whole farm in a

good year.

Our land was flooded, so we

hired a pump. He had only about 60 baskets left, which we

took to the administration—the entire lot, and not a

single basket was left. But they said, "This grain

is no good, we don't want it," and they made him

bring it all back.

Picture 28: "No farmer has enough to

eat."

|

Farmers now mix in dirt

and other stuff to increase the weight, so even

10 to 20% contain junk. Others bribe—a

couple of bottles of alcohol and maybe they get

10 baskets off the quota. Now

I've come to Thailand to do some trading, sell

medicines and stuff, instead of working there.

There's nothing to be gained from it.

|

While Rangoon Division’s "rice

bowl" is under extreme pressure to increase output,

farmers everywhere face the quota and forced labor on top of

debt and natural disaster. A Dawei Township farmer with four children

said:

I have 3 acres. Last year there

was a big flood and my entire farm was destroyed. I

replanted, but only got 130 baskets, instead of the

normal 200 to 250. We have to pay 12 baskets per acre as

quota, so that was 36 baskets. Because of the flood I

planted twice, so costs doubled. To pay and still meet

the quota meant I couldn’t even feed my family. I

was conscripted as a front line porter for five months,

during which my family had nothing to live on. The only

way was to borrow money. That is why we, the people,

never get sufficient food, never develop. Several in my

village have not been able to repay debts, and have

watched the government confiscate their land and transfer

it to other farmers. 24

Picture 29: "Now days many people have quit

farming because the government forces them to

raise cash-crops for export."

|

"I

was conscripted as a front line porter for five

months, during which time my family had nothing

to live on." |

We learned that the

government forces people to raise crops for export even when

they have nothing to eat. We read about this practice,

environmental problems and poverty in the Shan State:

Central Shan State around Hsi

Paw and Hsen Wi has big paddy plantations. But now days

many people have quit farming because the government

forces them to raise cash-crops for export. Paddy also is

becoming less beneficial for farmers. Agriculture

Department officials push new strains of rice unsuited to

the soil and cool weather. They also push soybeans and

peanuts as cash crops. But peanuts drain fertility, and

the soil must be left to regenerate or it will be

useless. The government pays less for produce here than

in central Burma. For all of these reasons, people are

quitting the land.

It seems that government

input to agriculture had always created problems. We read how

the BSPP failed to invigorate the land:

During the BSPP period,

especially in the early 1980s, farmers traded paddy for

chemical fertilizers under the quota system. At first,

crops were good, but over time the soil deteriorated and

the produce lost its flavor. More fertilizer was required

to get the same yield. Now much of this land no longer

produces; the chemicals caused permanent damage.

Nowadays, the only chemical fertilizer comes from China,

and only big landowners can afford it. Large areas once

cultivated in Hsen Wi are now barren, commodity prices

are rising and people are hungry. Disused land is taken

by the army.

We also have a report about

hunger in Arakan State, where the Muslim minority,

known as Rohingyas, are generally denied Burmese citizenship

and have been repeatedly swept into refugee camps in

Bangladesh. International human rights organizations noted:

Since most of the Rohingyas are

unskilled day laborers, one day of work without pay can

mean one day without food for the whole family. The

availability of work depends very much on the

agricultural cycle, and during summer there tends to be

very little work. In the past, Rohingyas traveled to find

work in towns, but since 1991 their freedom of movement

has been severely restricted… They thus have very

few sources of income to begin with, and since the dry

season also happens to be the best time for construction

work, when forced labor demands are most intense, the

burden on the Rohingyas is particularly acute. 25

All the above evidence

demonstrates food scarcity’s prevalence. However, we saw

that hunger is not only widespread, but also serious. It has

caused malnutrition and death in children, and increased

poverty for the whole family. An informant from a fertile

region of the Irrawaddy Division, recorded hunger’s

impact in his neighborhood.

In 1993 three children died a

couple of doors down from my house. All boys, they were

around 10, 8 and 6. The children had always been weak and

malnourished, especially in the last couple of years.

Their bellies were distended and their ribs stuck

out—like starving African children we saw in

magazines. Their knees were swollen and their calves were

sticks. Their skin was white, their lips pale. They often

had diarrhea. Their father worked cutting grass and

bamboo to build houses. They all died about a week

apart—I remember because I went to cut timber for a

week, came back and heard one had died. I went back to

the forest, came home the next week and another was gone.

Just one week later the third child died. We knew the

family well. I remember the family’s condition and

how this all came to pass.

Picture 30: "The soil must be

left to

regenerate or it will be

useless."

|

Map 2: Irrawaddy Division

(Click

to view full image)

|

Before they died, the

children were hungry for many years. Their family was caught

up in a political and economic crisis going on far outside

their village.

| "The

children had always been weak and malnourished,

especially in the last couple of years. Their bellies

were distended and their ribs stuck out—like

starving African children we saw in magazines." |

Their father used to grow

bananas, cucumbers, and watermelons on a small plot

about two miles outside the village. After the 1988

uprising, the government consolidated the village, so

the family had to move. Wild elephants ate all their

plants, and so he turned to cutting bamboo. He earned

about eighty kyat

per day, which might have been enough, but he only

got cash when bamboo traders came, so the family

sometimes went hungry. Also, at 45 he was getting

arthritis and couldn’t work every day. His

family of seven ate no more than mine of five, and my

children were younger. They begged for help

frequently. Of course, we pitied them and helped as

we could. Apart from rice, my wife gave them salt and

fish paste. When the children got

diarrhea nobody suspected anything serious. They took

some Burmese medicine, but that didn’t stop it.

Intravenous drips might have helped, but those cost

150 kyat or

so, and nobody could afford them. So they passed

away. The parents knew their children were dying, but

there was no health care or medicine. Their father

could only weep, heartbroken.

|

Reflecting on these tragic

deaths, the informant commented on the government’s role

in food scarcity:

I knew this was a wrong and

terrible thing. In my opinion, these children died from

starvation. If they had adequate food they wouldn’t

have died. And they weren’t the only ones, but I

don’t know the others’ details. In nearby

villages there was a minor epidemic. No matter how deep

in poverty, people are never excused from demands for

labor and money. This family had no alternative but to

struggle for survival every day, and so the children

died. 26

These narratives represent

the evidence presented to us. They are but a sampling of the

voluminous documentation we received. The next section

presents the last source of evidence we considered,

Burma’s cities and towns.

Hunger in the City Hunger in the City

Food scarcity also affects

Burma’s cities. The Tribunal heard of high food costs,

endemic corruption, forced labor, and dislocated rural

villagers drifting into cities in search of work or simply to

beg for food.

The cost of food rose

steadily through the 1990s. By 1998, most poor families in

the capital city could manage only one meal per day 27, though food security was by no

means elusive only to the urban poor. In January 1997 a

former office worker from Rangoon reported,

Picture 31: "We have to tell lies in order

to use our own property."

|

The biggest problem is

feeding our families. Nearly everyone in Rangoon

is struggling just to eat. Since we need money

for other things as well, usually we eat less or

eat very simply. This is a general economic

condition, not the problem of only poor people.

My house, for example, could be called

middle-class, but we face the same problems with

food as everyone else. 28 |

Poor urbanites earn their

food one day at a time:

Sundry workers include petty

vendors, tri-shaw drivers, hired laborers, and the like.

They earn between 50 to 180 kyat per

day, barely sufficient to cover the cost of rice. They

purchase only 2-3 pyi at

a time. Agricultural laborers working for the

government get only 20 kyat per day, but have the

privilege of purchasing 12 pyi of polished rice

for only 20 kyat. Sometimes they get afternoon meals

free. Most are women and teenage children. Only the

combined income of all members in a household enables

people to survive. 29

Civil servants

fare no better. While they may receive some benefits,

their income is sapped by a range of petty fees:

thirty kyat for monthly charge for volunteer fire

watch, fifteen for porter fees, two hundred for rice,

twenty for assorted benefits, ten for special

consumer discount rights, fifty to support festivals,

and two hundred for electricity. Half of one’s

salary may be lost to such fees.30 Compounding this loss are

stagnant wages from the government. Even a

substantial pay raise in the early 1990s was lost to

inflation:

That the government has

basically kept wages fixed only exacerbates these

conditions. A 1993 wage-hike averaging around 30%

for all civil servants has not helped to prevent

the slide in real wages. The official CPI was

running at 30% annually between 1989 and 1993,

and has risen since then. On the basis of private

estimates, prices of basic necessities in the

unofficial/black markets in Rangoon

and other major cities across Burma have been

rising at an average annual rate of over 100%

since 1989.

31

|

Picture 32: More visible are the social symptoms of

food scarcity: poverty and children dropping out of

school to work.

|

Government workers struggle

to eat in ways which affect everyone else. The Tribunal heard

that, perhaps inevitably,

Picture 33: "I saw people fleeing or being relocated

to the outskirts of town.

|

bribery and corruption are on

the rise. Civil servants are more interested in getting

outside incomes, looking for perks and extra cash from

their jobs, and any chance to leave for better jobs

outside the civil service. Private companies pay better,

especially foreign companies. An ordinary civil

servant earns between 900 and 1200 kyat per

month. Despite the discount rice they can not keep up

with inflation. 32 |

"An ordinary

civil servant earns between 900 and 1200 kyat per month.

Despite the discount rice they can not keep up with

inflation." |

A witness from Shan state

told us personally how poverty and corruption among

government teachers affects the nation’s education

system:

In 1988 we moved to Taunggyi,

but the education system wasn’t good there, the

teachers weren’t very enthusiastic. Because they

needed extra income, in the classroom they didn’t

teach the full curriculum. To pass the exams, students

had to pay the teachers for extra tutoring.

As in rural areas, these

various expenses and fees compound the authoritarian demands

by the government. Though the cities may at first glance

appear free from military pressure, security is not

guaranteed. The witness continued:

Picture 34: "When I was young I didn’t know

why they all came, but later I learned that no

villages were left in the surrounding countryside;

they had all been relocated."

|

In Taunggyi the government

widened the roads. People had their land confiscated

and their houses demolished. My family lived in a

small town and was never forced to relocate this way,

but every day I saw people fleeing or being relocated

to the outskirts of town. Nearby villages had to

relocate to suburbs, one or two miles out. When I was

young I didn’t know why they all came, but later

I learned that no villages were left in the

surrounding countryside; all had been relocated. When

I left, there was only one army camp, on a hilltop. I

went back to visit in 1994 and saw that outside the

two were many new military camps, set up on land that

used to belong to the people. |

AHRC has listed seven factors causing

hunger outside the war zones:

- Paddy

quota

The

government taxes farmers through a compulsory rice

purchase system based on unrealistic crop yields. The

quota is calculated according to acreage, not

production, and prescribes unrealistically high

contributions. Bad weather, flooding or crop failures

due to flawed government projects do not exempt

farmers. Many must buy rice then resell it for quota,

at considerable loss. Reform has failed.

- Agricultural

development

Programs

to increase yield have failed to realize food

security. Not only do farmers lose money, but they

must borrow money for fertilizers and farm equipment.

If they do not to comply with government regulations,

they risk land confiscation. Summer rice programs in

Irrawaddy Division and Mon State illustrate the

effects of these policies. Where crop yields do

increase, the government reaps the benefit: surplus

paddy is sold for export, rather than distributed to

hungry farmers.

- Land

confiscation

The

law empowers the government to take away

people’s land swiftly and efficiently 33. Apart from land

confiscation, small farmers abandon their land when

rice farming is no longer economically viable. They

become hired laborers whose daily wage can not

guarantee food security.

- Forced

labor

As in

civil war zones, the government conscripts

uncompensated labor on public works. Such work

includes servicing irrigation projects related to the

summer paddy program. This labor impedes food

security by reducing farmers’ time and capital

for agriculture.

- Economic

policy

The

government has created rice shortages by removing

paddy from the domestic market and selling it

overseas. Furthermore, this rice has been purchased

substantially below market rates. Rice prices have

inflated and the kyat has fallen, which

affects all food prices. The government has reduced

wages and benefits to the army and civil service,

contributing to endemic corruption by state

officials.

- Arbitrary

fees

Quite

apart from the rice quota system, administrative and

military officials levy a range of fees, fines and

arbitrary taxes. These payments are not part of an

official national tax structure, but are instead an

institutionalized form of corruption which uses the

formal structure of the state to support a shadow

economy.

- Inadequate

community health service

Malnutrition and illness are compounded by a general

lack of health services and high costs for medicine

and health care. Children have suffered hunger,

disease and death.

To recap: AHRC has presented a large amount

of evidence attesting to food scarcity across a range of

economic and political circumstances. This evidence comes

from firsthand sources such as depositions and statements, as

well as secondary sources analyzing politics and economy.

Many, though not all, witnesses appeared before us and

answered our questions. Overall, we find this evidence to be

informative, consistent, and credible, and therefore will

draw from it our findings and conclusions.

Government Response Government Response

Picture 35: Each smouldering grain of rice recovered from

the ashes of war testifies to the farmer’s

resilience.

|

After scrutinizing the evidence, we

arrived at certain tentative conclusions. Following the

principles of natural justice, we invited the Government

of Myanmar to respond before giving our final verdict. By

our letter dated 23 June 1999 addressed to H. E. Senior

General Than Shwe, Prime Minister of The Government of

the Union of Myanmar, we announced certain preliminary

conclusions, all indicating that there has in fact been

denial of food, largely through the actions of

government. 34 We

requested the government to reply by the end of July,

after which time the Tribunal would finalize its verdict.

The letter was delivered, but we received no response

whatsoever. Given this failure to reply, we are free to

proceed with our findings. If sometime in the future the

Government changes heart and submits evidence, it can be

included in any future proceedings or reports. |

| 1 |

|

A catalogue of material submitted to

the Tribunal, witness deposition, testimonies, and a

bibliography are attached as Appendices 2,3, 4 and 7

respectively. |

| 2 |

|

Saw Kwe Say, Report on the

Conditions in Free Fire Zones of Mudraw and Mone

Townships, 1996. |

| 3 |

|

AHRC, First Submission to the

People’s Tribunal on Food Scarcity and

Militarization in Burma, 1 February 1999, p. 73. |

| 4 |

|

"Confidential Report to Burma

Issues on taxation and extortion of villages in Kyauk Kyi

Township, Pegu Division," 17 October 1998. |

| 5 |

|

Karen Human Rights Group, Wholesale

Destruction: The SLORC/SPDC Campaign to Obliterate All

Hill Villages in Papun and Eastern Nyaunglebin Districts,

Chiang Mai: Nopburee Press, April 1998. |

| 6 |

|

AHRC, p. 73. |

| 7 |

|

See "The mountains of war," Testimony 1, Appendix 4. |

| 8 |

|

See "War and hunger in the

1990s," Testimony 2, Appendix 4. |

| 9 |

|

See "A village teacher," Testimony 4, Appendix 4. |

| 10 |

|

See the First Witness’

deposition, Appendix 3. |

| 11 |

|

See the First Witness’

deposition,Appendix 3. |

| 12 |

|

See "Forced Relocation," Testimony 23, Appendix 4. |

| 13 |

|

Adapted from Terror in the South:

Militarisation, Economics and Human Rights in Southern

Burma, All Burma Students Democratic Front, November

1997 |

| 14 |

|

See "Wandering in the

jungle," Testimony 13, Appendix 4. |

| 15 |

|

See "No living things," Testimony 14, Appendix 4. |

| 16 |

|

International Labour Organisation,

"Forced Labour in Myanmar (Burma). Report of the

Commission of Inquiry appointed under article 26 of the

Constitution of the International Labour Organization to

examine the observance by Myanmar of the Forced Labour

Convention, 1930 (No. 29). Geneva, 1998." |

| 17 |

|

AHRC, p. 132. |

| 18 |

|

See "Shouldering the

burden," Testimony 15, Appendix 4. |

| 19 |

|

AHRC, p. 139 |

| 20 |

|

See "Forced relocation," Testimony

23, Appendix 4. |

| 21 |

|

Win Hlaing, "Tenasserim Division:

Thayet Chaung /Ye Pyu Townships Rural Conditions,"

25 October 1998 |

| 22 |

|

See "The reality of agricultural

development," Testimony 24, Appendix 4. |

| 23 |

|

The New Light of Myanmar, 27

March 1995, reported on the dam's inauguration. It was

later covered in "Minister for A&I inspects

Ngamoeyeik Dam, paddy fields in Bago Division," New

Light of Myanmar, 6 September 1998. |

| 24 |

|

AHRC, p.181. |

| 25 |

|

Human Rights Watch/Asia; Refugees

International, Bangladesh/Burma – Rohingya

Refugees in Bangladesh: The Search for a Lasting Solution,

August 1997, pp. 11-12. Further information on food

scarcity can be found in "Rohingya said to be

fleeing famine," The Nation, 11 May 1997 and

Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, "Starvation Looms

in Arakan," Newsletter, April 1997. |

| 26 |

|

See "Food scarcity in the

delta," Testimony 26, Appendix 4. |

| 27 |

|

American Embassy Rangoon, p. 33. |

| 28 |

|

"The Inside Perspective," Burma

Issues, January 1997. |

| 29 |

|

AHRC, p. 186. |

| 30 |

|

National Coalition Government of the

Union of Burma, Human Rights Yearbook 1996, July

1997, p. 221. |

| 31 |

|

Mya Maung, "The State of the

Burmese Economy under Military Management," in Human

Rights Yearbook 1995, National Coalition Government

of the Union of Burma, May 1996, p. 33. |

| 32 |

|

Confidential Report to Burma

Issues, July 1997. |

| 33 |

|

Mon Information Service (Bangkok), Abuses

Against Peasant Farmers in Burma, July 1998. |

| 34 |

|

The letter is attached here as Appendix

1. |

Return

to Top

|