|

FINDINGS

In light of the evidence before us, as

summarized in the previous section, we may render our

findings. The People's Tribunal finds that indeed food

scarcity is widespread and serious in Burma today.

Provisionally, we find Burma to be militarized, and that a

causal nexus links militarization to food scarcity. This

section of the report details why we arrive at these

conclusions.

On the Right to Food On the Right to Food

| The right to food, as defined by

the International Bill of Rights, has been denied to

a large but unknown number of people. As explained in

the scope of the Tribunal, the right to food invests

certain positive obligations in all sovereign states.

Burma has never ratified the relevant international

legal instruments, but this failure to publicly

accede diminishes neither the validity nor the

universality of the concepts they represent. In fact,

the Government has committed itself to them in its

own public statements. |

Picture 36: "They fed what they had to the

children, and the adults fasted."

|

The Right to Work The Right to Work

The evidence consistently and convincingly

illustrated that the state prevents people from working to

achieve food security. Farmers are prevented from using their

land, water and other natural resources to provide sufficient

food. They are not free to choose when, how and what to

cultivate. They are not free to devote their own labor to

food security. Communities in armed conflict zones are

prevented from using their labor, land and natural resources

to achieve food security. Farmers in non-conflict zones are

compelled to appease the state first, and feed themselves

second. Regardless of their own economic well-being, farmers

and others are required to provide goods and services to

state institutions, especially the army.

State rhetoric conflicts diametrically with

reality, but what Burma’s government says about food

security demonstrates an awareness of its obligations. For

example, in March 1998 the government reported to the World

Food Summit, an intergovernmental conference, that "The

Government of Myanmar remains totally pledged to the

achievement of food security for all. 1" The report outlines a series of commitments

conforming to the Summit’s Plan of Action:

| "The

Government of Myanmar remains totally pledged to the

achievement of food security for all." |

Commitment

One: We will ensure an enabling political,

social, and economic environment designed to create

the best conditions for the eradication of poverty

and for durable peace... which is most conducive to

achieving sustainable food security for all... Commitment Two:

We will implement policies aimed at eradicating

poverty and inequality and improving physical and

economic access by all, at all times, to sufficient,

nutritionally adequate and safe food and its

effective utilization...

|

To pursue

poverty eradication, among both urban and rural poor and

sustainable food security... the Government have laid

down agriculture sector policies as follows:

- Free choice

of crop production

- Provision of

right to cultivate to those who develop new

agriculture land or who are cultivating the land

- Provision of

land ownership to the perennial crops growers, as

long as they are producing commercially...

The Tribunal finds that despite these

commitments to ensuring farmers’ rights and food

security, the government consistently undermines its own

stated goals and obligations. The evidence shows that in

civil war zones farmers are simply denied the right to

cultivate. Farmers in eastern, central and lower Burma who

would prefer to plant beans and pulses, relatively quota-free

crops, are nevertheless compelled to grow paddy. The

government prescribes land for rice production and

confiscates land from farmers who do not grow paddy. We find

that these policies negate farmers’ self sufficiency,

deny their right to work and deprive them of food.

Paddy Procurement Paddy Procurement

| The law empowers Burma’s

government to purchase for redistribution or resale a

percentage of all paddy. A compulsory nationwide

program conducted by a government agency, buying

substantially below market price, it is effectively a

crop tax. The rationale for the low price paid, about

half of market value, is to feed the armed forces and

provide discounted rice to civil servants.

Furthermore, MAPT exports paddy earning foreign

currency. |

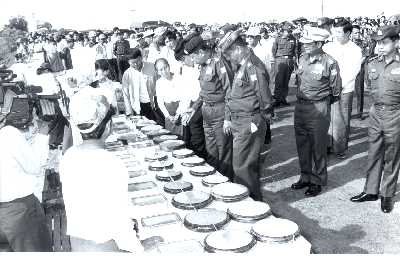

Picture 37: In practice, the government denies rice

to the very people who grow it

|

Despite its theoretical merits, the paddy

quota fails to promote food security. In practice, the

government denies rice to the very people who grow it, people

who don’t have enough to eat. Hungry farmers grow rice,

but the State takes it away without otherwise providing for

their food security. This is severe injustice.

The paddy quota is inherently unfair,

unrealistically and inflexibly assessing how much rice

farmers can spare. Furthermore, through this coercive system

the government pays little for rice destined to bring high

profits in overseas markets, with no commensurate payment to

farmers whatsoever. Corruption and quota pressures mean

sometimes farmers must sell even more paddy than calculated.

Agents subtract moisture content, and thus demand greater

volume. Farmers have little choice but to accept these

adjustments. In addition to the MAPT quota, local authorities

compel farmers to sell more rice at MAPT prices. This

black-market quota may amount to several percent of paddy

production. In remote areas, the army conducts virtually all

paddy procurement, arbitrarily and with force.

It appears that this system is a major

cause of inflation in Burma’s economy. Expensive rice

means higher costs for all food, and rural and urban people

alike can not feed themselves adequately. Given the uniform

evidence detailing how paddy procurement siphons rice from

rural households, and the economic hardship this system

creates for farmers, the Tribunal judges it a significant

factor in food scarcity

Forced

Labor Forced

Labor

Forced labor has been Burma’s most

widely documented and roundly condemned human rights

violation.2 To maintain our scope of

inquiry, we will confine this discussion to forced

labor’s relationship with food scarcity. In a word, the

State’s demand for compulsory, uncompensated labor

denies the right to food.

Picture 38:"My oldest daughter, who is eleven,

always went to do forced labor while we parents looked

for food."

|

Under threat of violence, civilians

must work on roads, railways, dams, military

installations and a variety of other infra-structure

projects. Typically, local authorities (civil servants in

non-civil war zones, the army elsewhere) send an order to

village leaders specifying the time, place and nature of

the work, as well as the number of people required. It

could be for one day or one month. Often the order is to

recruit one worker from each household. People unwilling

or unable to work may find a substitute or pay a cash

fine. |

Witnesses testified to the economic

hardship incurred by this inflexible, time-consuming and

sometimes dangerous work. Conditions of forced labor vary

throughout the country. Once again, the difference depends on

war zones. Portering for the army, minesweeping and serving

military installations increase worker risks. Several porters

attested to being underfed, neglected and abused. Wherever

forced labor takes place, it affects agriculture, household

income and food in three ways. First, it reduces the amount

of time and energy people spend in productive work to feed

themselves. Second, it extracts cash from households. Last,

the actual work forces people to face hunger.

Forced labor is a common practice with

severe repercussions on household economy and food scarcity.

The evidence before the Tribunal from a variety of sources

indicates that it is a major drain on Burma’s rural

economy and a significant cause of food scarcity.

Counter-insurgency Counter-insurgency

| Nowhere does the state deny food

more blatantly than in combat zones. The Tribunal

finds the counter-insurgency program to have

absolutely decimated food security in and around

combat zones. The strategy is simple but effective:

stop food, funds, recruits and intelligence from

reaching insurgents by severing ties between

guerrillas and civilians. Since the guerrillas

generally operate in small mobile units, the Four

Cuts fall on rural villages in six ways. |

Arbitrary

and severe violence has destroyed countless rural

villages, scattering people throughout the jungles. |

The Army

Destroys Food and Crops

Military operations in the civil war zones

target the rural food supply. Apparently, the army’s

justification is that this food, or some portion of it, is in

fact being supplied to insurgent forces, and therefore must

be withheld. The army does attempt to distinguish between

food intended for civilian consumption and food allegedly

destined for the rebels. Instead, the army targets crops

which provide the local food supply, in fear that if

harvested, this rice would feed guerrillas. Tilling the soil,

planting, tending fields, harvesting—all phases of

agriculture are subject to attack.

The Army

Displaces Civilians

Arbitrary and severe

violence has destroyed countless rural villages, scattering

people throughout the jungles. Where the army conducts

intermittent raids but has no permanent bases, civilians may

choose to remain in or near their villages, hiding when

soldiers approach. Familiar with the local terrain, hunting

conditions and edible plants, native inhabitants attempt to

survive despite the loss of their homes and farms. The Four

Cuts have thus created a phenomenon of internally displaced

people (IDPs), living with perpetual food scarcity.

The Tribunal finds that the severest cases

of food scarcity, including reports of starvation, occur

among IDPs made homeless by the military strategy.

Furthermore, this sector of Burmese society has the fewest

alternatives when facing a food crisis. The army’s

presence makes travel hazardous, even when people cross the

border into Thailand as refugees.

The Army

Relocates Villages

| Relocating human

settlements is a major element of the strategy,

uprooting hundreds of thousands—perhaps

millions—of people over the years and in many

cases devastating the rural economy. This is coerced,

involuntary relocation, enforced by the army.

Typically, a village either receives written order or

a visit by military officers, who command it to move.

|

Picture 39: "They told us troops in the hills

have orders to kill anything they see. We are haunted

by this."

|

The Tribunal found that some areas, such as

the eastern Pegu Yoma mountains, have known strategic relocation for

nearly three decades. Major forced relocation in Pegu

Division began in the 1970s, when hill villages were moved

close to army posts, and numerous restrictions were placed on

travel out of the relocation sites. In 1979, one hundred

refugees from Thaton district crossed over the Thai/Burmese

border and became the first group of Burmese refugees to

enter Thailand. 3

Picture 40: "This year we ran from the army four

times."

|

But forced relocation is not

confined to any one region; it happens wherever the

army faces the threat of insurgency. One of the most

comprehensive and damaging forced relocations ever is

currently underway in the Shan State, where over

300,000 people have been moved for strategic

purposes.4

At the relocation sites villagers are called on to

work for the Burma army, such as building stockades,

doing chores at army posts, guarding roads, building

railroads serving as porters, and a variety of other

tasks the local military designates. However, many

people ordered to relocate do not move to the new

sites. They may migrate to cities and become hired

workers. |

We find that relocation has profound

effects on food security. Moving people cuts them off from

their land and natural resource base, subsistence

farmers’ lifeline. The military neither compensates

people for these losses nor designates new land. In the words

of a Tatmadaw officer explaining relocation to villagers,

"This is military rule… you stay where we tell you

to stay." 5

Furthermore, food is tightly restricted in

relocation centers, depending on the army’s perception

of insurgent threat and whether rations actually exist.

Relocation creates serious long-term food scarcity, rather

than seasonal hunger arising from military incursions or

heavy taxes at harvest time. A relocated family has lost its

land, and with it the children’s future security in the

rural economy. Economically, they must begin again, often

starting from zero.

The Army

Expropriates Cash and Materials

| Relocated or not, people must

provide cash, goods and services to local military

authorities. Refugees sometimes cite these

unrelenting and excessive demands as reasons why they

left. Although witnesses call it taxation, there is

no connection to any national revenue or excise

department. Quite to the contrary, it is an ad hoc

practice serving military needs, and individual

soldiers’ arbitrary and sometimes capricious

demands. Construction materials, food, livestock,

liquor and virtually any other items are expropriated

or taxed in this way. The army has also made

civilians responsible for security by threatening

heavy fines for any local rebel activity. The

military promises economic ruin for any village

tolerating guerrilla action. |

Picture 41: "This is military rule… you

stay where we tell you to stay." |

On Militarization On Militarization

The Tribunal recognized prima facie that

Burma has a military government and that the army is

prominent in national affairs. These facts of militarism were

never in doubt, but nonetheless have been amply demonstrated

in our foregoing discussions on the right to food. Our

inquiry does, however, assess militarization as

defined in the scope: military ideology, values and social

structures pervading and dominating the economic, social and

political life of the country. Militarism describes an army

pursuing its conventional role with much vigor;

militarization describes the pursuit and capture of all

society.

| We can not study this

problem’s complexity solely by surveying food

scarcity. One would have to define Burma’s

military institutions, their history, activities,

structure and philosophy, then examine in detail

their social, cultural and psychological effects. One

would need to examine how military ideology is

propagated through folklore, education and mass

media. Ideally, one would interview military

officers, rank-and-file soldiers within the Tatmadaw

and its opposition. |

Do

the Tribunal’s findings on denial of food

indicate militarization of Burma? We

find that they do. |

Such a definitive inquiry exceeds our

scope; it is complex and important enough to warrant a

Tribunal of its own. Here, we will confine our assessment to

the inquiry at hand: denial of food. We therefore pose and

answer the following question: Do the Tribunal’s

findings on denial of food indicate militarization of Burma?

We find that they do.

Routine State Functions Routine State Functions

We found two major causes of food scarcity

to be paddy

procurement and public works projects. Although military

involvement should not be necessary for these routine

functions of government, both fall under explicit and

implicit military control.

In

theory, paddy procurement is a contract between farmers and

the state. Tax collection is a normal and reasonable state

duty. To this end, MAPT and associated agencies

have staff and offices throughout the country, performing

their duty in cooperation with town and village authorities.

Furthermore, the national police force, to the extent that it

is separate from the army, deals with violations of tax law.

Therefore, there is no apparent institutional need for the

army.

Nevertheless, the paddy quota has been

militarized through coercive military force. Evidence showed

that soldiers took rice from farmers late for the quota, and

that military officials physically and verbally assaulted

farmers for not producing enough paddy for quota. For

example, in 1997 the Mudon Township Council set a January

quota deadline. When farmers were late, soldiers "simply

went to houses and barns and took the grain by force." 6 In areas without MAPT

officers or where the army must provide for itself, the quota

is replaced by arbitrary taxation, levied with impunity and

military violence. Unlike rice collected by the government

then redistributed to the army, this tax is consumed locally

by the "tax man" himself. Clearly, the military

usurps taxation as a routine and legitimate function of

government.

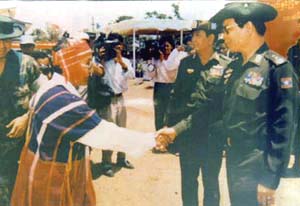

Picture 42: Militarism describes an army pursuing its

conventional role with much vigor; militarization

describes the pursuit and capture of all society

|

Forced labor also reveals

militarization. Like tax, public works such as building

and maintaining roads, dams and canals are routine state

functions. When critics attack forced labor, Burma’s

government objects to a foreign misread of unique and

necessary national traditions. However, regardless of

whether forced labor is customary or necessary, people

resent the danger and economic burden it creates,

particularly food scarcity. The evidence shows people not

opposed to the public works projects per se, or

even to donating their labor, but to the military’s

management approach. Rural traditions like collective

farming exemplify that labor could be arranged in other

ways. Once again, routine administration does not require

military excess. Yet it is overwhelmed by military

authoritarianism, and suffers because of it. |

Militarization of Agriculture Militarization of Agriculture

Burma is an agrarian society. Farming is

not just an occupation, but a way of life. Conceivably, high

taxes and unpaid labor might constrict agrarian living

without threatening the foundation of subsistence

agriculture: fertile land and productive work. Yet there has

been a militarization of agricul-ture through continuous

preference for military priorities over farmers’ needs.

| The Tribunal finds that buying

paddy, building dams, increasing production and

selling rice on the world market all put military

interests above food security. On one hand, these

imply development and open-market reform. On the

other hand, the hand of reality, they have been a

human rights disaster. These policies would not be so

uniformly terrible if planned and carried out

democratically. The essential problem is that

militarization simultaneously depends on farmers and

negates their way of life. |

Picture 43: "People are only thinking of how to

get a little food to fill their stomachs."

|

The government correctly identifies

agriculture as Burma’s economic foundation, and formally

specifies development as a national objective.7 Officially, the government’s Four Economic

Objectives are

- Development

of agriculture as the base and all-round development

of other sectors of the economy as well

- Proper

evolution of the market-oriented economy

- Development

of the economy inviting participation in terms of

technical know-how and investments from sources

inside the country and abroad

- The

initiative to shape the national economy must be kept

in the hands of the State and the national peoples

Furthermore, promoting rice cultivation

makes sense as economic policy, ensuring a homegrown staple

diet. The problem is that various development schemes and

policies never challenge the assumption that Burma needs to

recruit, feed and equip a huge army. This army’s simple

existence strains the rural economy: recruiting farmers to be

soldiers; feeding them with other farmers’ rice; and

buying materiel with rice export. Agriculture has become the

basis for military buildup. Controlling and exploiting

agricultural production have therefore become military goals.

The military pursues these goals in a spirit of conquest and

militarism.

Picture 44: Promoting rice cultivation makes sense as

economic policy, ensuring a homegrown staple diet

|

This is militarization, not mere

militarism, for two reasons. First, it is a thorough,

systematic and nationwide orientation towards

military control of agriculture, replete with

violence, intimidation and military fanfare. Second,

and perhaps more telling, is that military structure

and ideology take over government, abrogating

farmers’ self-sufficient way of life. This was

clear with the Ngamoeyeik dam, where the

government’s hierarchy meddled with

farmers’ expert knowledge of land and water,

resulting in flood, drought and farmers simply giving

up. When the people complained, "What are you

doing? We can’t even live here anymore!"

officials replied that they didn’t know, they

were just following orders. It was nearly impossible

for farmers to participate in decisions about

agriculture. Militarization’s

values—buildup of the armed forces, hierarchy,

and blind obedience—seem incompatible with

agrarian living. |

Military in the Media Military in the Media

Food scarcity also suggests militarization

through government’s control of state media. Again, it

is necessary to distinguish simple militarism, which

might use mass communication to honor or celebrate the armed

forces, from militarization, in which propaganda goes

a step further, promoting military attitudes and priorities.

Militarism depicts the army’s forceful presence;

militarization prepares the whole society to think and feel

like soldiers going into battle. Mainstream opinion is made

to reflect goals normally confined to the army.

| Every day the state reiterates

these goals, which are printed in newspapers,

announced on television and repeated at public

events. Apart from the Four Political, Four Economic

and Four Social Objectives of the State is the

People’s Desire, a propaganda campaign begun in

1996. The sum of these slogans is supposed to

represent the common will. The People’s Desire

comprises four commitments to safeguarding the

nation: 8 |

Picture 45: Militarization prepares the whole society

to think and feel like soldiers going into battle.

|

- Oppose those

relying on external elements, acting as stooges,

holding negative views.

- Oppose those

trying to jeopardize stability of the State and

progress of the nation.

- Oppose

foreign nations interfering in internal affairs of

the State.

- Crush all

internal and external destructive elements as the

common enemy.

| The government claimed these

statements to be the product of mass meetings

featuring speeches, patriotic oaths and unanimous

ratification of the People’s Desire. As army

propaganda, there is nothing remarkable here. All

militaries are assigned to protect the State. The

People’s Desire is remarkable because it is not

supposed to be military propaganda, but a summary of

civilian wishes. It embodies several ideas: that

civilians and the Tatmadaw are indivisible, that

what’s good for the army is good for the people,

and that true victory will come when the populace

truly adopts militant nationalism. Conspicuously

absent from these aims are political negotiation,

poverty eradication and similar "hearts and

minds" tactics. Food security, land rights,

health care and education, desires that some of

Burma’s people expressed to the Tribunal,

apparently have no place. |

Picture 46: "We are the lucky ones, to be able

to leave."

|

State media further confuses the roles of

soldier and farmer by continuously reporting on military

officials’ input to agriculture. Inspecting fields,

checking irrigation ditches, making speeches to farmers,

reviewing machinery and "leaving necessary

instructions" wherever officials go—all are public

acts which reinforce the message of army leadership in rural

life.

If standard propaganda featuring military

speeches and parades reveal militarism, then formulations

like the People’s Desire, which superimpose military

thinking on the whole population, reveal militarization.

Popular Opinion Popular Opinion

We found the last indicator of

militarization to be witness statements. Witnesses repeatedly

expressed that Burma is dominated by military, and that

rights and freedoms they wish for are therefore impossible.

People believe Burma is hopelessly militarized, and that

military influence forces them into misery. This viewpoint

was especially convincing in testimony from refugees, who

weren’t merely opining on politics, but explaining why

they left their homes, gave up their land and now live in

extreme poverty. The military’s predominance is real and

pervasive enough to affect people’s most important

economic and social decisions.

Such statements make three points. First is

the perception that military rule is a nationwide reality

with serious implications for everybody. The second is that

military rule is absolute, leaving no viable alternative

other than flight. Not a single witness expressed faith in

the justice system or even mentioned Burma’s courts.

Lastly, traditional values of rural society have collapsed:

the state has turned people against each other. It has

replaced trust and cooperation with desperate competition for

survival. All of these elements can be seen in Saw

Roman’s direct testimony to the Tribunal:

Many people have experienced far

greater suffering than us. We are the lucky ones, to be

able to leave. I consider Burma my home and my land, but

because of gross injustice and abuse, we are forced to

run away. We grew rice until this year. I even planted a

new crop, but we had to leave it all. If we harvested

early to pay for the journey people would have suspected.

So we lost everything. 9

Picture 47: "Crush all internal and external

destructive elements as the common enemy."

|

Saw Roman’s family might have

survived another season; perhaps next year’s

quota will decrease; the neighbors may not be

informers after all. Speculation is immaterial,

because Saw Roman’s view of life in Burma has

been militarized. He is resigned to the supremacy of

the armed forces. Justified or not this resignation

is shared by many, and demonstrates

militarization’s advances on national psyche. |

| 1 |

|

Ministry of Agriculture and

Irrigation, The National Report to CFS on the

Implementation of the World Food Summit Plan of Action

Until End 1997 (Union of Myanmar), The Government of

the Union of Myanmar, March 1998, p. 9. |

| 2 |

|

The most comprehesive treatment of

forced labor in Burma is found in the International

Labour Organisation’s "Forced Labour in Myanmar

(Burma)." |

| 3 |

|

Saw Nyi Nyi, "Burma Issues

internal report," 1997, p. 5. |

| 4 |

|

See Shan Human Rights Foundation, Dispossessed:

Forced Relocation and Extrajudicial Killings in Shan

State, April 1998. |

| 5 |

|

Second Strategic Command officer,

Colonel Aung Naing Tun, to a meeting of headmen at

Thandaung, Papun Township, Karen State, in 1995.

"Confidential Report to Burma Issues: Summary of

1995 offensive in Papun Township," 1997. |

| 6 |

|

Mon Information Service, "Human

Rights Report 1/97: The Forced Purchasing of Paddy in Mon

State," May 1997, Report 1. |

| 7 |

|

The Four Political Objectives

are

1) Stability of the State, community peace and

tranquillity, prevalence of law and order; 2) National

reconsolidation; 3) Emergence of a new and enduring State

Constitution; 4) Building of a new modern developed

nation in accord with the new State Constitution.

The Four Social Objectives are

1) Uplift of the morale and morality of the entire

nation; 2) Uplift of national prestige and integrity and

preservation and safeguarding of cultural heritage and

national character; 3) Uplift of dynamism of patriotic

spirit; 4) Uplift of health, fitness and education

standards of the entire nation. |

| 8 |

|

As broadcast daily on TV Myanmar. |

| 9 |

|

See Saw Roman’s deposition in Appendix 3. |

Return to Top

|