|

SCOPE OF INQUIRY

Concerned by frequent and serious reports

of hunger in Burma, the Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

invited us to sit as members of the People’s Tribunal on

Food Scarcity and Militarization in Burma, and requested us

to hold an inquiry. We are aware that there is military

dictatorship in Burma, that there have been human rights

violations throughout the country, and that such violations

continue even today. However, in this inquiry we are not

concerned with all such abuse. We are mainly concerned with

whether the right to food has been denied to people in Burma,

and if so whether this denial owes to a militarization of

Burmese society.

This section presents the terms and

concepts basic to our inquiry. It also summarizes the history

of food production and military rule provided us by AHRC.

The Right to Food The Right to Food

The right to food is

recognized by both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and

Cultural Rights, passed by the UN in 1966 (ICESCR). Article

25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reads:

Everyone has the right to a

standard of living adequate for the health and well being

of himself and of his family, including food, clothing,

housing and medical care and necessary social services,

and the right to security in the event of unemployment,

disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of

livelihood, in circumstances beyond his control.

The Declaration further

states that member nations should "by progressive

measures, national and international… secure their

universal and effective recognition and observance." The

primacy of right to food is also established by Article 11 of

the ICESCR, which provides:

1.) The States Parties to the

present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an

adequate standard of living for himself and his family,

including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the

continuous improvement of living conditions. The States

Parties will take appropriate steps to ensure the

realization of this right, recognizing to this effect the

essential importance of international cooperation based

on free consent;

The States Parties to the

present Covenant, recognizing the fundamental right of

everyone to be free from hunger, shall take, individually

and through international cooperation, the measures,

including specific programs, which are needed;

| Failure

to safeguard the right to food is as bad as failure

to protect life |

To improve methods of

production, conservation and distribution of food by

making full use of technical and scientific

knowledge, by disseminating knowledge of the

principles of nutrition and by developing or

reforming agrarian systems in such a way as to

achieve the most efficient development and

utilization of natural resources; |

Taking into account the problems

of both food-importing and food-exporting countries, to

ensure an equitable distribution of world food supplies

in relation to need.

Under the international legal system,

States have a duty to respect, promote and fulfil all basic

human rights. If protecting life is what human rights are all

about, it must be said that life cannot be sustained without

food. Food is not just a commodity, but the guaranteed right

of every person. Failure to safeguard the right to food is as

bad as failure to protect life; if multitudes are denied

food, mass starvation and death are bound to ensue.

The State’s obligation to protect the

right to food goes beyond providing a morsel of food for

every hungry mouth. Instead, it means States must perform

certain positive obligations. Their obligations include:

- To respect people’s

right and freedom to control their resource base,

namely land;

- To eliminate any form of

involuntary servitude that restricts the freedom to

choose an adequate resource base from which to obtain

sustenance;

- To protect this freedom and

resource base from encroachers;

- To assist people who are

unable to take care of their needs;

- To eliminate discriminations

hampering free access to food; and in no event to

indulge in any act of commission or omission which

will endanger people’s capacity to produce food

and have access to it.

| Within the international legal

framework, non-performance of the duties mentioned

above, or any of them, or deliberate refusal to

comply with them, would constitute denial of the

right to food. At the same time, the Government of

the Union of Myanmar has not acceded to most

international legal instruments, including the

International Covenant on Economic Social and

Cultural Rights. This raises the question of

applicability. The Tribunal’s view is that a

distinction can be made between the legal instruments

of human rights as the letter of law, and the

universal truths about human life and society which

these laws help to articulate. This is especially

pertinent to such a basic right as food, the

universality of which can not be reasonably

challenged. Failing to ratify an international treaty

may preclude other governments’ right to censure

in certain forums, but it does not exempt Myanmar

from the obligation to respect and establish basic

human rights. Moreover, the government has

voluntarily committed itself in non-binding

declarations, plans and obligations to protect the

right to food. The universality of human rights and

the government’s awareness of its

responsibilities therefore render the Government of

Myanmar accountable for allegations of abuse. |

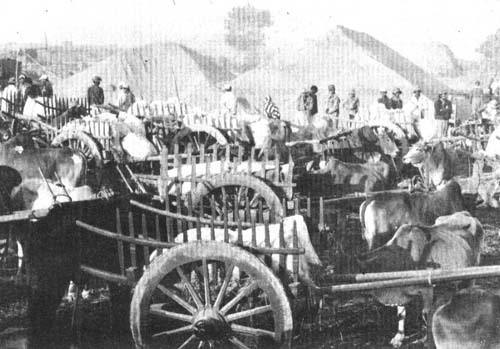

Picture 1: Food scarcity

refers to inadequate access to the necessary amount

of food as measured in real terms. Picture 1: Food scarcity

refers to inadequate access to the necessary amount

of food as measured in real terms.

|

AHRC has measured the denial of the right

to food in Burma terms of "food scarcity." This

phrase denotes the absence of sufficient food to maintain a

healthy and active life 1.

Food scarcity refers to inadequate access to the necessary

amount of food as measured in real terms: whether people

actually have food to eat. Food may be produced and sold

abundantly, but if it is too expensive or not available

locally then people will have no food on their tables. It is

the opposite of food security. Clinical malnutrition and

death from starvation may be extreme effects, but are not

required to demonstrate food scarcity. More visible are the

social symptoms: poverty, children dropping out of school to

work, crime, corruption and other communal or environmental

damage created by the desperate search for a reliable food

source.

Rice Rice

Any investigation into hunger must take

into account agricultural production and distribution. AHRC

has provided the Tribunal with a background to Burma’s

agricultural economy, summarized briefly below.

Picture 2: "Bad

harvests in 1966-68 resulted in short supply of

food."

|

Rice is the staple crop and staple

food, and is the commodity which determines food

security or scarcity. Burma’s agricultural

economy has weathered four eras of rice production

and distribution: feudal, colonial export,

nationalized, and post-socialist. Importantly, none

of these historical shifts tells the full story.

Because the country is politically and geographically

diverse, significant sectors of the agricultural

economy remained unaffected by these historical

changes. This is particularly true in the distinction

between lowland rice production, by which farmers

cultivate rice paddies flooded by monsoon rains, and

highland swidden agriculture, in which non-irrigated

fields are cultivated on hillsides. To generalize:

lowland cultivation provides a surplus crop to be

sold and traded; growing highland rice generally

produces a subsistence crop for local consumption.

The four eras of Burma’s agricultural economy

generally refer to changes in the production and

distribution of lowland paddy. |

| Feudal agriculture provided a

community’s food and whatever tribute was due to

the monarch or his local vassal. Generally, the

subsistence economy depended on three factors: enough

cultivable land, communal labor and a local natural

resource base to provide the necessities of life. The

"rice tax" due the royal court, its army

and small civil service was more or less of a burden

depending on proximity to the capital (or feudal

lord), total output and the specific demands placed

on a farming community. |

"Around

1960 one kilogram of rice cost 0.5 kyat. In 1966-69 it cost 28

kyat, 56 times more." |

With colonialism came the rice

export economy. Under British administration, vast areas

of lower Burma were cleared for export rice production,

and by the 1920s Burma became the foremost supplier of

rice to the world. In 1939 Burma was still the leader,

putting 3 million tons of rice on the international

market that year. Much of it was grown in the Irrawaddy Delta

and exported from Rangoon.

Under the socialist regime, which took over

in 1962, rice production was nationalized. The government

attempted to redistribute productive lands under nationally

administered, locally managed collective farming. The general

ineffectiveness of this program combined with the fertility

of Burma’s soil meant that the changes posed little

threat to food security, despite population growth from 17

million just after World War II to 24 million in 1962.

However, poor harvests in the late 1960s tested nationalized

rice production’s flexibility in a crisis:

Bad harvests in 1966-68 resulted

in short supply of food. Starvation was experienced for

the first time in the known history of Burma. Even during

the four years (1942-45) of war, food had not been

scarce. For the first time in the lives of the people of

Burma, the word famine expressed itself in real life.

Parents sold their children for some rice… Around

1960 1 kilogram of rice cost .5 kyat. In

1966-69 it cost 28 kyat, 56 times more.2

In good times and in bad, the government

was a major rice consumer. It purchased a percentage of all

rice produced at a fixed rate, regardless of most

fluctuations in the rice market. As in pre-colonial times,

the government procured rice to provision the army and sell

at a discount to civil servants. Throughout the shortages of

the 1960s, the government maintained its purchase rate of 3

kyat per kilogram, or almost one-tenth of the going market

rate.

Picture 3: "The government pays little for rice

destined to bring high profits in overseas

markets."

|

Trouble in the rice market

triggered the end of the socialist-styled

agricultural economy. By 1987 another food crisis

loomed, and the government abandoned its strictest

controls on the rice market. In August 1997 rice had

risen to 15 kyat per kilogram, the highest price

since the 1960s. Fearing possible famine, in

September the government lifted the ban on

harvest-time rice trading, in place since 1962. The

market price of rice was cut in half. |

The post-socialist era has retained central

planning and control of food production. Farmers are still

required to sell a percentage of their rice to the government

at discount prices. This paddy procurement system is

implemented by Myanma Agricultural Produce Trading (MAPT), a

state agency which, along with other arms of the bureaucracy,

inherited the duty from its socialist predecessor, State

Corporation No 1. MAPT’s national structure reaches down

to the village, where it designates paddy land and collects a

fixed quota based on land area. This quota rose steadily from

1988 until 1995, when it was fixed at 12 baskets per acre in high rice-producing areas such as

Irrawaddy Division (reports of quotas set at 15 or even 18

baskets are not unknown). Around this time the government

paid one-third to one-fifth the going market price for rice

purchased under the quota system.

An inherent flaw in this system is the

government’s quota calculation based on arable land area

rather than amount of rice actually planted or harvested.

Farmers who work poor land or for other reasons produce an

imperfect crop are not exempt from the quota. They fulfil

their obligation by supplying paddy bought on the market. In

these cases, the difference between the relatively high

market price and the low government purchase rate results in

a net loss for farmers.

Households which fail to fill the quota

face a variety of consequences. While arrests and beatings

have been reported, more common is the confiscation of paddy

land, for redistribution to other farmers more likely to

produce. Farmers have also been sent to labor camps to work

off their debt. In Irrawaddy Division, local military

authorities are said to have ordered no milling of harvested

rice for consumption or trade until entire villages filled

their quotas. Lastly, farmers have been threatened, scolded

and publicly abused by government rice procurers dissatisfied

with their quota.

Quota rice is not only used to provision

the army and the civil service, but sold on the international

market. Since 1988 there has been a renewed emphasis on

agricultural production for export. The main strategies are

to increase the land area under cultivation, increase

productive capacity through a variety of irrigation and

agricultural development projects, and license commercial

ventures to grow rice for export.

| In 1994 the government announced a

major new drive to increase rice exports fourfold,

but in the first years of its plan was forced to buy

rice at market value to make up for the shortfall of MAPT-procured quota rice. The World Bank

estimates that in 1994-95 rice farmers lost about one

quarter of their gross income because of MAPT

procurement. This mass purchase of an additional 3%

of the nation’s rice over and above the quota

raised its domestic market value. Following this

experience, the government became slightly more

cautious in purchasing rice for export. In 1997

government purchase rates rose to almost one half the

market price for top-quality rice. A temporary

relaxation of the strictest aspects of the quota rule

and a reduction in land confiscation also saw the

total amount of rice procured fall by 21% in 1996-97. |

Picture 4: Corruption and quota pressures mean

sometimes farmers must sell even more paddy than

calculated.

|

The government may have accepted that its

export plans will only be realized when the total amount of

paddy produced in Burma increases to satisfy the both the

domestic market and the MAPT quota, and leaves a surplus

bound for foreign shores. In a speech to mark World Food Day

1997, Minister for Agriculture and Irrigation, Lt-Gen

Myint Aung, explained:

Being endowed with equitable

weather conditions and abundance of land and water

resources, Myanmar has made great accomplishments in the

production of food through the joint effort of the

Government and the people... A tremendous amount of

capital has been invested for the implementation of

increased food production programs. We have been engaged

[in] the development of virgin lands, expansion of

cropping areas and increasing the cropping

intensity...Food policy adopted for the country is

aim[ed] at supplying [a] sufficient amount of food for

the entire nation and at the same time to guarantee

better health and social well being of the populace. 3

Picture 5: "They took video where the crop

looked good, where it was green and ripe."

|

The government has launched

agricultural development schemes throughout the

country, but especially in the Irrawaddy Delta. The

centerpiece is the summer paddy program, in which the

traditional single rice crop per year, sown in the

rainy season and reaped in the cool season of

October-December, is followed by another crop raised

and reaped in the hot season. The summer paddy scheme

has several elements: development of irrigation

systems such as dams and canals, introduction of high

yielding hot-season rice strains, and use of new

fertilizers, pesticides and machinery to cope with

the technical complications of the new crop. |

These tactics have created two new burdens

for farmers. The first is the labor needed to build roads,

small dams and irrigation ditches. State-directed,

uncompensated labor is common practice in Burma. Farmers who

work on these development projects have less time to tend

their crops or other subsistence activities. Secondly, the

chemical ingredients of the summer rice program are not

distributed free to poor farmers, but are sold to them.

Farmers who don’t buy the necessary materials can not

participate in the program; their unproductive land,

officially designated for double-cropping, is reassigned to a

more able household.

| The socialist-era reassign-ment of

arable land to productive farmers has taken a new

twist in the late 1990s: corporate rice farming. In

January 1999 the government announced that 200,000

acres of paddy land in the Irrawaddy, Rangoon and Magwe Divisions had been transferred to

nine unnamed entrepreneurs licensed by the government

to reclaim "wetlands and vacant, fallow and

virgin lands." It further added that "More

wetlands and vacant, fallow and virgin lands are

being reclaimed to extend cultivation to ensure rice

sufficiency for the people" in a campaign to

increase wet-season paddy land by two million acres,

and summer paddy by an additional four million. 4 |

Picture 6: Development schemes never challenge the

assumption that Burma needs to recruit, feed and

equip a huge army.

|

Recent US Department of Agriculture

statistics affirm statements by the Burma government that in

1998-99 rice export once again drove national farming policy.

There was a substantial export increase in 1998; by November,

86,233 metric tons of paddy had been exported, compared to

only 15,328 for the whole of 1997. 5 These

reports coincide with rising national production targets, to

be achieved in part by contracting big parcels of land to

entrepreneurs.

| "Militarism

is distinguished as being of a more material,

physical quality…while militarization is

predominantly an ideological orientation..." |

Despite efforts to increase rice

production, independent reports indicate that in the

early 1990s, over 30% of Burma’s children were

suffering from malnutrition. Furthermore, anecdotal

reports from throughout the country confirm that many

people simply don’t have enough to eat. AHRC has

provided some of these reports to the Tribunal; most

are publicly available. Perhaps one million Burmese

refugees and migrant workers reside in neighboring

Thailand, many reporting food scarcity as their

primary reason for flight. |

Militarization Militarization

| The Asian Human Rights Commission

has submitted that food scarcity and hunger exist

because of militarization. In defining this term,

AHRC has distinguished between militarism and militarization,

the critical difference being the social and

ideological force the latter exerts on the normative

life of society: |

Reports

indicate that in the early 1990s, 31% of Burma’s

children were suffering from malnutrition |

Militarization

should be understood as the process whereby military

values, ideology, and patterns of behavior achieve a

dominating influence on the political, social, economic,

and external affairs of the State; and as a consequence,

the structural, ideological, and behavioral patterns of

both the society and the government are

"militarized." 6

Thus, the distinction between

militarization and militarism:

militarization…

denote[s] the spread of military values (discipline and

conformity, centralization of authority, the predominance

of hierarchical structures, etc.) into the mainstream of

national economic and socio-political life. Militarism is

distinguished as being of a more material, physical

quality…while militarization is predominantly an

ideological orientation, often leading to military

leadership of civilian organizations and institutions. 7

| So we have been presented with a

distinction between militarism as a visible

characteristic of state and militarization as a more

abstract interpretation of how those characteristics

affect the nation. From these definitions the

Tribunal understands that a degree of militarism is

already known to exist. Burma’s military

government, armed conflict and suppression of

political dissent are all facts which we recognize at

the outset. However, a large and active army, the

State’s use of violence and even military rule

are traits of militarism which can exist without

extreme pervasion of military culture and

polarization of people from the state. AHRC has

sought to establish before us that what has taken

place in Burma is not mere militarism, but

militarization in the full sense. This is the issue

we will consider. |

AHRC has sought to

establish that what has taken place in Burma is not

mere militarism, but militarization in the full sense |

Rise of the Tatmadaw Rise of the Tatmadaw

The AHRC has outlined Burma’s modern

political history to help define the scope of the Tribunal.

This history can be summarized as follows.

The modern nation of Burma was forged when

a variety of feudal states were consolidated by British

colonial rule. Before colonial times, there were no fixed

boundaries around a single encompassing nation or kingdom.

Instead, peoples living in and around the Irrawaddy

River basin existed under the rising and falling influence of

Burman, Mon, Shan, Arakan, Siamese and other kingdoms. Furthermore, huge

highlands were home to various peoples without large-scale

polities, especially Kachin, Chin, and Karen

peoples, as well as numerous related and unrelated groups.

Throughout the 19th century, however, England

fought a series of wars with the Burman empire in a campaign

to make Burma the easternmost province of British India. By

1890, the last Burman king went into exile, and colonial

administration was established. The eastern border with Siam

was more or less demarcated, Assam and Manipur were retained

as parts of India, and the northern and northeastern

frontiers with China roughly set. Burma was created not as a

sovereign nation, but as a colonial province of British

India.

British Burma was thus a mosaic of peoples

and places brought for the first time under a single state.

The peoples of Burma received the new regime with varying

reactions, some resisting colonialism outright and others

welcoming it as a turn in their political favor. British

interest lay in profitable export of teak and rice, and in

controlling the eastern extreme of British India. European

expansion ended with World War II and the invasion of Burma

by Japan. A group of Burman nationalists known as the Thirty

Comrades seized the war as an opportunity to oust Britain.

They established the Burma Independence Army (BIA), led by

General Aung San, which assisted Japan on the understanding

that once the British had been routed, Burma would achieve

independence. However, doubts about the sincerity or

viability of the Japanese pledge led the BIA to switch sides,

and by the end of the war Burma remained a British colony.

Picture 7: The Tatmadaw developed a political

identity as defender of Burma’s unity… |

World War II also crystallized

modern ethnic nationalism. Burmans saw the war as the

beginning of a drive for independence, a campaign

which was ultimately successful. Chins, Kachins and

Karens provided pivotal support to the Allies

throughout the war, raising their status within the

colonial administration and exposing them to

techniques of modern warfare. Furthermore, the

BIA’s initial cooperation with Japan entailed

retribution against those who aided the British,

including the ethnic minorities. Thus the war

created, renewed or intensified ethnic tensions

between Burmans, whose monarch had been banished and

who had been subjugated under colonial rule, and the

minorities, whose subjugation under the Burman kings

had been somewhat relieved by the British. |

When Britain granted independence to Burma

in 1948, questions over autonomy for ethnic-minority

inhabited areas remained unresolved. General Aung San, who

headed a controversial provisional government, was

assassinated along with his entire cabinet just before the

British withdrew. Within months the country was covered with

nationalist and communist movements. The Burma army, or Tatmadaw, was thus born into the role of suppressing

the disunity of a nation which had never been unified to

begin with.

Throughout the 1950s the Burma army’s

power grew steadily, while political inroads to resolving

Burma’s many conflicts were few and led nowhere. In 1958

a military-led caretaker government assumed control, led by

General Ne Win, one of the Thirty Comrades. In 1962 Ne Win

consolidated his power through a complete military coup. For

three decades of Ne Win’s rule, the Tatmadaw developed a

political identity as defender of Burma’s unity against

internal enemies. The Burma army cast itself as savior of the

nation’s integrity.

Politically, the period between 1962 and

1988 was Ne Win’s experiment with socialism. Single

party rule fell to the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP),

which nationalized agriculture and industry and turned Burma

into a "closed" country. BSPP legalized itself in

1974 through a new constitution. In 1988, with Burma facing

economic ruin, Ne Win retired from his leading role in

national politics. In August many people took to the streets

calling for greater reform, invoking a harsh military

response. Thousands of demonstrators, including students and

workers, were killed or fled to the frontier areas. A junta

of hard line military officers staged a coup, reasserting the

army’s prominence. In September 1988, the State Law and

Order Restoration Council (SLORC) replaced the BSPP and its

pretensions to both socialism and quasi-civilian rule.

Despite holding a promised election in 1990, the military

refused to cede power to an elected parliament, persecuted

its rivals, especially the National League for Democracy

(NLD), and maintained tight control on all political dissent.

The 1990s saw the Tatmadaw expand, modernize, and begin to

open the nation’s economy to foreign capital.

| Insurgency continued throughout

the BSPP and SLORC eras. The Karen rebellion, which broke out

near Rangoon in 1949, gradually drifted eastward to

the Thai frontier. The Kachin Independence

Organization maintained control over the highlands in

northern Burma. Meanwhile, the adjacent Shan State

was home to ethnic nationalist movements, drug

warlords and the once-powerful Communist Party of

Burma. In 1974 the Tatmadaw expanded the "Four

Cuts," an anti-insurgency program designed to

cut civilian support for guerrillas. The brutality of

this campaign fuelled further resistance and cemented

the belief that the Tatmadaw was intent on genocide,

making total autonomy of minority peoples the only

secure political destiny. SLORC’s determination

to quash Burma’s insurgency saw a series of

political and military successes throughout the

1990s. It concluded cease-fire agreements with

several opposition groups and won significant

military victories, especially along the Thai border. |

Picture 8: In 1974 the Tatmadaw expanded the

"Four Cuts."

|

| |

|

Picture 9: Throughout the 1990s the Tatmadaw grew

both in size and expenditure

|

Throughout the 1990s the Tatmadaw

grew both in size and expenditure. In 1989-90 the

army stood at 175,000 men but doubled to 350,000 in

1995-96. In the same period, the civil

service increased by only six percent. Indeed, a 1997

estimate put one in every 32 eligible people in the

military. The government’s target is 475,000

troops—larger than the US army and one of the

biggest standing armies in the world. The American

Embassy estimated defense spending to be at least

half of total government expenditure, at 8-10 % of

recorded GDP. 8

In 1988-89, the year SLORC formed, Burma spent 1.8

billion kyat on defense, constituting 22.9% of

recorded government spending, equivalent to 2.3% of

recorded GDP. By comparison, from 1993 to 1996

defense constituted about 40% of government spending.

The government reported that in 1995-96 for every

kyat spent on development in frontier areas more than

26 kyat went to the Tatmadaw. Beyond this substantial

piece of the national budget, the Tatmadaw receives

goods and services of uncalculated value: |

The Ministry of Defense receives

but does not pay for about one-fifth of Burma's centrally

generated electricity. The Defense Ministry also

purchases large amounts of fuel far below market prices.

In FY 95/96,

the Defense ministry purchased at least 12 million

gallons of fuel, at about 20 kyat per gallon for diesel

and 25 kyat per gallon for gasoline, for which the market

prices were about ten times higher. In addition, a

substantial share of the GOB's

declining real expenditures on health is said by health

industry experts to be used to provide medical services

to military personnel, and is not included in the defense

budget. The Defense Ministry also receives large amounts

of rice at a steep discount from the market price… 9

| Today, despite decades of armed

resistance, the military remains in firm control of

Burma’s political and economic scene. The

Tatmadaw has maintained its leading role in

Burma’s government, impervious to growing

international concern for human rights and political

freedom. The population, at about 45 million, has

virtually no legal options for political opposition,

although a number of illegal anti-government groups

operate throughout the country. Burma’s Tatmadaw

continues to pursue its vision of a unified,

"peaceful, modern and developed" nation led

by strong and vigilant military heroes. |

Picture 10: "They burned our houses and food

supplies and it’s plain to see that we could

never stay on there."

|

The Tribunal will consider food scarcity

and the militarization of Burmese society against this

background of a prominent and growing army. Certain political

facts are undisputed: Burma has a military government; this

government is autocratic; armed conflict exists within the

country; and civilians report that atrocities are committed

against them in the course of this conflict. Our inquiry is

to determine whether the right to food has been denied to the

people of Burma, and if so whether the military dictatorship

and the administration it controls are responsible. To make

this determination, we must evaluate AHRC’s charge that

the right to food has been denied, then judge whether there

is a nexus between this scarcity and military encroachment.

| 1 |

|

For more discussion of food scarcity

and related terms, se FAO’s The State of Food and

Agriculture, and Bread for the World’s Eighth

Annual Report, cited in the Bibiliography (Appendix

7). |

| 2 |

|

Shwe Lu Maung, Burma: Nationalism

and Ideology, Dhaka: University Press Ltd., 1989. pp.

56-7. |

| 3 |

|

"More Food Being Grown to

Eradicate Hunger and Malnutrition," New Light of

Myanmar, 17 October 1997. |

| 4 |

|

"Nineteen entrepreneur groups to

reclaim 203,000 acres in Ayeyawady Division," New

Light of Myanmar, 19 January 1999. |

| 5 |

|

US Department of Agriculture,

"Burma's monthly rice trade and price update for

September, 1998," GAIN Report (#BM8013, 8

October 1998). |

| 6 |

|

Churches Commission on International

Affairs, Militarism and Human Rights, Geneva:

World Council of Churches, 1982, p. 5. |

| 7 |

|

Jim Zwick, "Militarism and

Repression in the Philippines," Working Paper

Series, Montreal: McGill University Developing Area

Studies, 1982, p. 4. |

| 8 |

|

American Embassy Rangoon, Foreign

Economic Trends Report: Burma, 1997, September 1997,

p. 15. |

| 9 |

|

The American Embassy’s statistics

are not official, but are a compilation of embassy,

Myanmar government and World Bank/IMF figures. The

embassy’s report outlines the flaws inherent in all

statistical data on Burma, including a general

incompleteness of all data, exchange rate distortion,

omission of defense-related imports and overstatement of

international debt service payments. |

Return

to Top

|